He had actually ducked inside the People’s Republic of China to close the deal for a presidential visit. Perlstein writes:įor all his listeners knew, when Henry Kissinger disappeared from the diplomatic press corps’ radar the next day on an official visit to Pakistan, it was just as his handlers claimed: that he was indisposed with a stomachache. In Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America, his compelling, rowdy and incisive analysis of Nixon’s rise and fall in the turbulent ‘60s and early ‘70s, Rick Perlstein conjectures that the significance of Nixon’s Holiday Inn speech wasn’t recognized until years later. Though he warned that America’s economic power was waning and forecasted the need to “take the first steps toward ending the isolation of Mainland China from the world community,” Nixon – who had been a crafty poker player while serving in the Navy - wasn’t showing many cards. Trouble was, no one at the Holiday Inn fully fathomed what “Tricky Dick” was up to. Nixon hinted at a future shift in foreign policy that would climax in his unprecedented visit to China. To that ability, of course, Nixon added a sociopathic disregard for truthfulness and legality that would make Ariel Sharon look like an honest man.In a July 6, 1971, speech before media executives at a Holiday Inn in Kansas City, Missouri, President Richard M. That was the emotional basis for Nixon’s ability to unite everyone who felt excluded by the exuberance and anger and hope of the ’60s, who felt assaulted and threatened by the changes. Perlstein describes Nixon in similar terms: Someone who from boyhood onward felt that the elite looked down on him, that he was out of fashion through no fault of his own, and who managed to fuse the anger of all the others who felt left out into a political movement. His politics deepened all the divisions in Israel, and we suffer for it till today.

His resentment was pitch perfect for those Israelis who felt the country’s elite had denied them respect. Menachem Begin saw himself as unjustly ostracized and excluded from power. It was the crippled Franklin Delano Roosevelt, for example, who could tell a crippled America there was nothing to fear.” Sometimes a leader can uplift for this reason sometimes he or she can release a bitter flood. Perlstein's portrayal of the relation between Nixon's inner furies and the political furies of the 1960s and early '70s bear out a thesis I've argued in the past : Some leaders succeed because their “…personal struggles resonated powerfully and subliminally with a wide public.

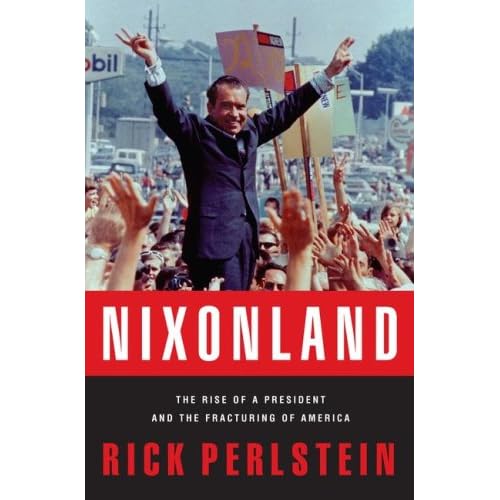

I've just finished reading Rick Perlstein’s Nixonland, an impressive depressing portrait of my native country in the years just before I decided to move to South Jerusalem.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)